Building a learning course: Interslavic by Zagreb method (part 1)

Many people are interested in a some sort of interactive course/textbook helping them learn Interslavic. The most popular question is, of course, about the Duolingo course (short answer: doesn’t look feasible at the moment, but the most of blame should be directed at Duolingo, not at the Interslavic community), but it makes more sense to create a “stand-alone” practice course, not related to Duolingo.

Do other conlangs happen to have interesting learning apps? Turns out, there’s a great Esperanto course which is configurable and hack-able, so it’s possible to use its engine for Interslavic.

Now, I’m going to get a quick FAQ out of the way, and then the rest of this post is going to be devoted to my attempts to convert this Esperanto course into an Interslavic course.

what is Esperanto? what is Interslavic?

Both Esperanto and Interslavic are auxilary constructed languages (“auxlangs” for short), although aimed at different audiences and having different weak and strong sides. Esperanto is an international auxlang, but Interslavic is a zonal auxlang, designed to be close to various Slavic languages.

Both languages are quite easy to learn. The grammar of Esperanto is deliberately made very simple and regular, and vocabulary is mostly derived from European internationalisms. On the other hand, Interslavic is easy to learn if you already speak any Slavic language, but non-speakers will have a harder time with it.

what is Zagreb method?

Zagreb method is a teaching method developed by Zlatko Tišljar and other Esperantists from Croatia. It can be described as an attempt to simplify and streamline the learning course while getting the most bang for your proverbial buck. Zlatko Tišljar analyzed a large corpus of Esperanto texts and isolated a list of 500 most frequent morphemes, which was enough to cover more than 95% of that corpus.

“Morpheme” means either root (e.g. “fort” which is encountered in words related to strength or being strong), prefix (e.g. “mal” which is used for negation) or suffix (e.g. -o: the common ending of nouns). So, the word “malforto” consists of three different morphemes and could be translated as “the weak one” or “weakling”.

The Zagreb method course was designed to not use anything not contained in that 500-item list. The course is short (only 12 lessons), but thanks to the aforementioned word frequency distribution it provides student with a worthy toolbox. Thanks to the simplicity of Esperanto’s grammar and syntax, this toolbox should be able to crack most Esperanto sentences; why carry a large backpack when a small utility belt suffices?

so, how it works?

The source code of esperanto12.net is available on GitHub under very permissible CC-BY-4.0 license. The content is stored in YAML files; later a Python script is used to convert them into a number of static HTML files written into an aptly named html_generiloj directory. Afterwards, the site is uploaded to some server: unfortunately, I’m not sure I understand how deployment process works here. However, it seems that around 2016 everything was very straightforwardly hosted on GitHub Pages, so I assume the current process isn’t dramatically more complicated than that.

The course supports a number of languages. That is, you can select English/Turkish/Czech/Italian/etc and view the course in your preferred language. This is achieved via the same YAML files in the enhavo folder, most of which are language-dependent. Here it is important to understand how these files correspond to various course pages, so let’s take a look at the structure of typical lesson. Each lesson consists of:

- a text in Esperanto; no separate translation is provided

-

an explanation of the grammar related to the lesson. It’s not just translated into a target language, it’s adapted to it. For example, the first lesson has a section on alphabet and pronounciation; unsurprisingly, it’s very long and detailed in English, meanwhile the counterpart for Slovak speakers basically boils down to “read everything as in Slovak except for

ĝĥĵand diphtongs withuŭ”. On the other hand, the section about the definite articlelain English is noticeably shorter than either of Croatian, Russian, and Slovak translations. Interestingly, the Arabic version of the penultimate lesson contains an additional clarification regarding the difference betweenporandpor ke; no other translation has it. - Exercise 1, which is of “translate this word into your native language” variety. Here, the translator should provide the set of correct answers (unsurprisingly, more than one translation could be considered valid).

- Exercise 2, which is a basic gap-filling exercise; no need to translate this one. It should be noted that not all gaps are words; the student is sometimes asked to add a suffix or prefix to a “partially” provided word (for example, an ending corresponding to the correct verb tense or noun gender).

- Exercise 3, which requires student to translate from target language to Esperanto. Here, the translator should provide two variants of the original text: the first one that sounds natural and the second one that uses Esperanto sentence structure, suitable for word-by-word translation exercise.

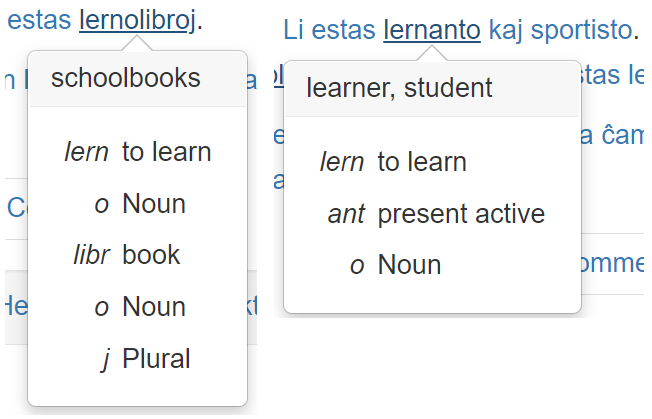

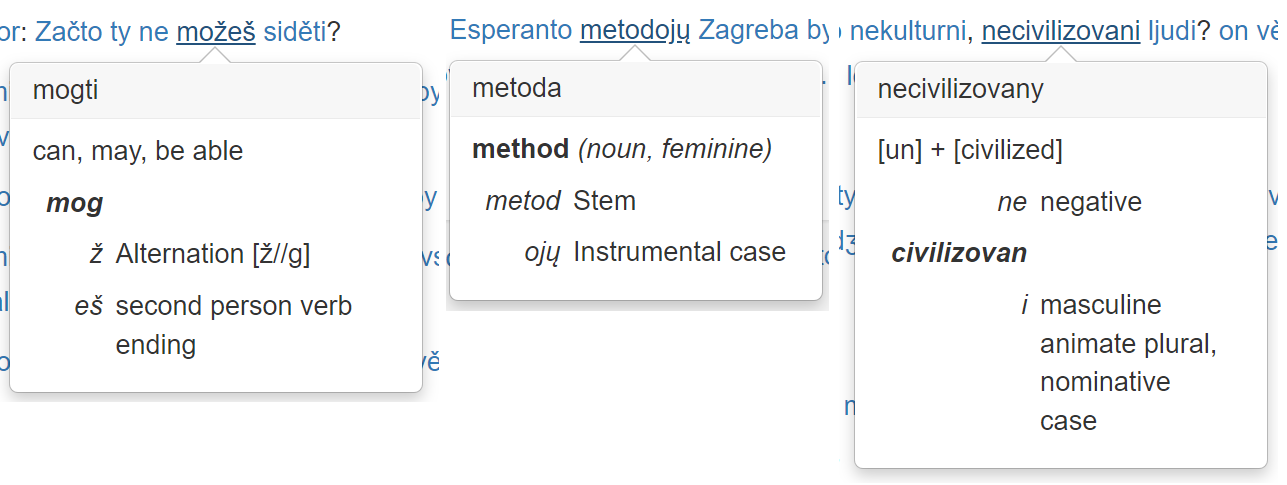

The neat thing is hovering tooltips providing translations and morpheme-by-morpheme breakdown of meaning. Although Zlatko Tišljar made no mention of modern Javascript frameworks in the 1980 book, the popover technology provides perhaps the best illustration for his original insight of studying Esperanto using morphemes.

For some reason this functionality is present in Exercises 1 and 3 (where it can be used to effortlessly cheat) but is absent in Exercise 2. To me it looks backwards, but maybe I’m missing something.

For some reason this functionality is present in Exercises 1 and 3 (where it can be used to effortlessly cheat) but is absent in Exercise 2. To me it looks backwards, but maybe I’m missing something.

The content of popover window is generated automatically from another bunch of YAML files with names like adverbo.yml, prefikso.yml, radiko.yml, sufikso.yml, koloro.yml, etc. Aside from the vorto.yml file, the information is organized into small categories relating to part-of-speech, word/morpheme status (roots, prefixes, suffixes), membership in a natural collection (e.g. day of the week).

Is it a good fit for Interslavic?

From the very beginning, the Interslavic project and the Interslavic community made a good effort to preserve the links between Interslavic and natural languages. This includes (but probably isn’t limited to):

- the flavorisation scripts by Jan van Steenbergen;

- the very impressive work of volunteer translators that gave us the Medžuslovnik;

- the ongoing work of translating JvS website into other languages;

- the attempt of Discord community to write a set of language specific crash courses (see

#pisanje-prva-pomočchannel on the Discord server).

The Esperanto course treats translations as a first class citizens, which makes me optimistic.

Moreover, the general paradigm of “let’s take some amount of words/morphemes that covers 95%+ of known texts” by necessity implies that the most words obtained that way will be (or should be; let’s add them if they aren’t) included in Medžuslovnik. Together with their translations into several Slavic languages; isn’t it nice when the most work is already done for us?

Continuing the path of integrating the existing resources… for a long time I was thinking about improving the Jan’s flavorization machine to make it take into account morphological information. Let’s take Croatian speaker for example: I think seeing how nogami changes into nogama and then back into nogami again gives something hard to obtain from just a formal grammar specification. And the interactivity already present in the Esperanto course paves a way for something like this.

As another plus, I think static websites are nice. My blog is hosted on Jekyll, so you can tell :) On the other hand, one can be unhappy about the frontend stack. The HTML pages use Bootstrap.js that depends on jQuery, which, as I am told, is positively ancient and out-of-fashion nowadays. Well, on the other hand these are mature, respectable technologies, making problems really easy to troubleshoot with the help of Google. I’m not a frontend specialist, so this is fine enough for me.

Possible problems

There are some aspects of Esperanto course that would be harder to adapt to Interslavic. The most serious and obvious one is, of course, the fact that we have no such course available to “interactivify”. No lesson plan, no exercises, no word list, no top-N most common words, nothing (at least nothing available under the required license).

For now, I’m going to ignore this small detail. I’ll take a particularly hilarious story out of the infamous Russian Course textbook by Alexander Lipson and translate it into Interslavic. That’s gotta be the content of my first lesson.

(the story about Cultural Entertainment Park, to be specific. If you are curious: the Russian version, the English version)

We’ll tackle the problem of course content later. For now, let’s focus on the technical proof-of-concept.

Morphology

Several quick mock-ups demonstrating what information could be provided in a popover window

Several quick mock-ups demonstrating what information could be provided in a popover window

In Esperanto, each morpheme has a single meaning, so you can build the meaning of “lernanto” out of the meanings for “lern”, “ant”, and “o” without any additional context, in a completely automatic way. There’s still some ambiguity regarding the splitting an Esperanto word into buiding blocks; for example, “revidi” should be parsed as “re + vid + i” and means “to see again”, but “respekt” is atomic, it doesn’t mean “to spekt again”.

For this reason, YAML files related to Esperanto text have every word already divided into constituent morphemes, which should be done manually. Then, during the building of HTML files, for each morpheme a lookup is performed, fetching it’s translation from the prefikso.yml, radiko.yml, sufikso.yml (and so on) files.

This will not work for Interslavic. For example, the -a ending could be a “feminine, singular, nominative” marker or a “masculine, singular, genetive/accusative” marker (as in “žena vidi muža”). Also, many Interslavic prefixes could be stand-alone prepositions, such as “za”.

Hence, the whole structure of prefikso.yml, radiko.yml, sufikso.yml needs to be re-done from the scratch. The YAML files are also should be radically changed: in order to correctly parse “žena vidi muža”, much more information is required. Providing such information manually is bound to be very annoying. Thankfully, I already have Interslavic pymorphy2 dictionaries available, which makes it possible to infer a lion’s share of this data automatically.

Still, the result isn’t exactly what you would call human-readable. The YAML files are going to be large and unwieldy; one can edit them slightly, if needed, but producing them isn’t really feasible. This creates a need for another processing step: now, YAML files are intermediate artifacts instead of a source. Ideally, the source should look like a plaintext file, not an array of metainformation. Of course, we will encounter a lot of cases where some word’s morphological attributes require manual disambiguation; I’ll prefer this additions to be inline and non-intrusive.

I would like to obtain something like this, eventually:

žena vidi {3per} dobrogo {masc accs} mųža {accs}

where the first comment disambiguates between “vidi” as in “she sees it” and “vidi!” as in imperative “I order you to see”, and the second and third ones clarify that “dobry mųž” has an Accusative case instead of Genitive. Let’s mentally shelf that goal for later; for now we pretend that there’s no ambiguity so no {} are required.

Input method

The Esperanto course has the following disclaimer above the every input field:

The Esperanto letters can also be written like this: cx, gx, hx, jx, sx and ux.

This is, of course, aimed at folks who are unable or unwilling to install a custom Esperanto keyboard. No doubt we want something similar for Interslavic, since gatekeeping in a beginner course makes no sense. Unfortunately, here we encounter another conceptual problem.

The “extended etymological” alphabet of Interslavic (also known as “Medžuslovjansky Plus”) has no ASCII-friendly representation. I’m not speaking about some sort of official standard; I’m saying that there’s not even a single proposed system available anywhere. In contrast to Esperanto that has a limited set of diacritics (circumflex accents in ĉ, ĝ, ĥ, ĵ, ŝ and a breve in ŭ), Interslavic Plus has both more letters and more types of diacritics.

Namely: ring above (å), caron (č š ž ě), dot above (ė ȯ), ogonek (ę ų), acute accent (ć ľ ń ŕ ś ź ĺ t́ d́, the three last symbols are also sometimes written like ľ ť ď), and upper stroke (đ, could be written as dž with almost no information loss). One could also make a pretty good case for the inclusion of ḓ and ǥ/ħ. Out of all these types, only carons could be maybe described as having a consensus ASCII representation: č = cz, cx; š = sz, sx; ž = zs, zx, zh; ě = ie, ex. Well, as long as you don’t look at Žž too closely.

So, how can we adapt Esperanto input method to this mess? I see some potential solutions, none of them are ideal:

1) Ignore etymological alphabet: this is the simplest option, but I dislike it.

The etymological alphabet is optional in the sense of “you do not need it to write Interslavic”, but I believe that the knowledge of it is pretty damn useful (for example, see this). In my opinion, the good middle point is something like “I know this word should be spelled językoznańje, but typing these letters is annoying, so I’ll just write jezykoznanje”.

Therefore, the beginner course is the very place where the use of etymological alphabet should be encouraged instead of discouraged: otherwise, how are people supposed to learn it? One could make an argument for discarding additional diacritics in a casual chatroom but discarding them in a learning environment seems like a huge waste.

2) Use a TeX or RFC 1345 convention for diacritics, as described here. This will lead to weird stuff like “be<gaju;c’i pe.s ima be<le zu;by”.

3) Use some sort of “universal” magic symbol that means “I know this letter should have some kind of diacritic mark on it, but I refuse to elaborate” (you can interpret Esperanto X-System as a type of this: both ŝ and ŭ are written like sx/ux).

Similarly, we can use Javascript to detect if user has Alt/Ctrl key pressed and modify the resulting symbol. That way <ALT+z> becomes <ž> (or <ź>, depending on the expected word) even if user has no special keyboard layouts or customizations.

4) Accept text without diacritics (“zena vidi muza”) but fix it visually after input in order to establish a link in the student’s mind (so it’s possible to notice how the word is supposed to look like when spelled “correctly”). Requires some sort of “check!” button which makes interface more clunky.

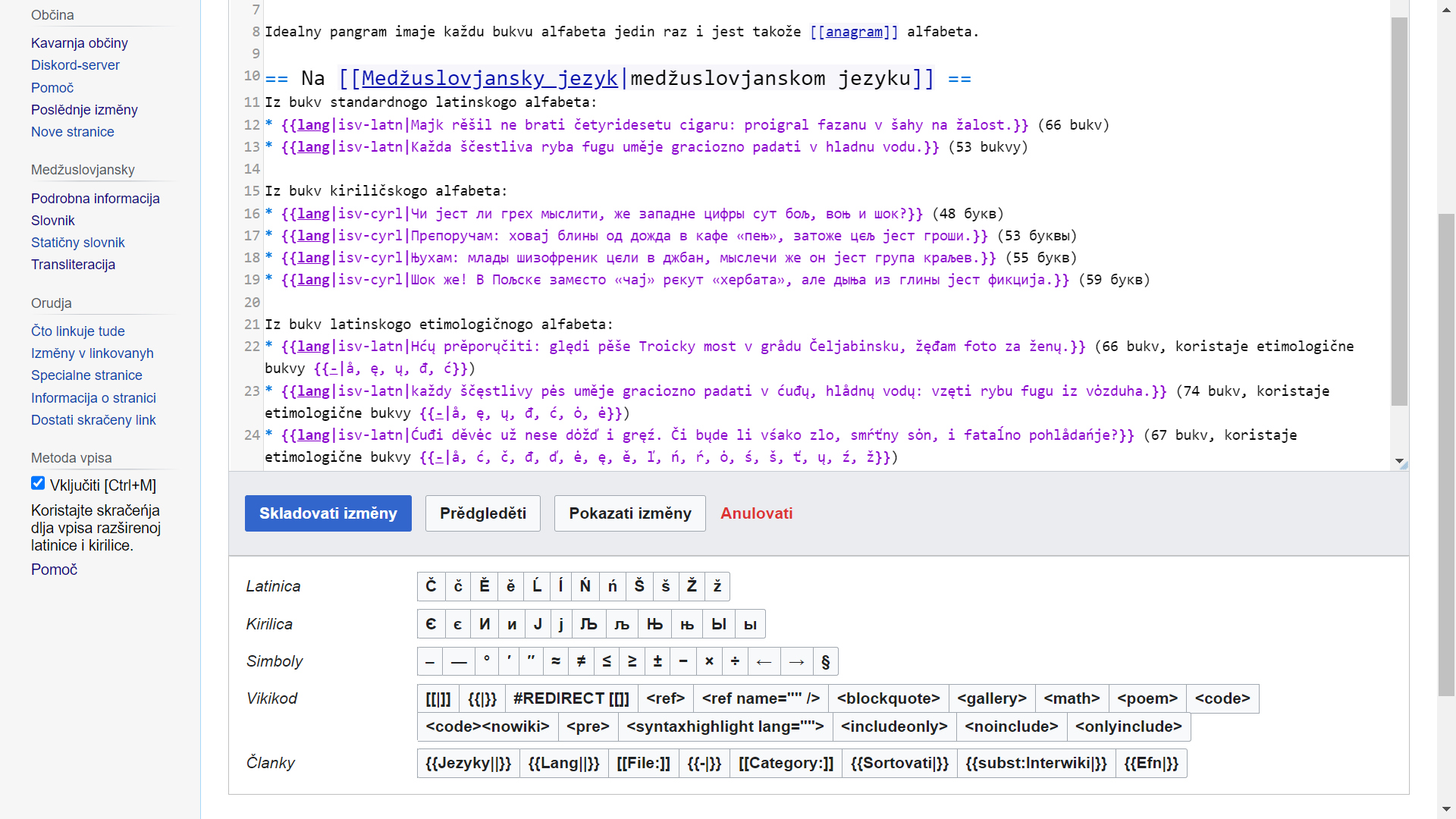

Aside: how ISV Wiki does it

As an aside, Interslavic Wiki (also known as Medžuviki) has a similar problem with inputting non-ASCII characters. To make matters even more complicated, ISV Wiki wants to support both Latin and Cyrillic alphabets (it has an interactive widget to transliterate between two scripts, so everyone could read articles in their preferred script), and the availability of characters needed for standard (non-etymological) Cyrillic is awkward (standard alphabet uses Єє Јј Ыы characters that never go together on common Cyrillic keyboards).

Medžuviki uses only standard Latin and Cyrillic alphabets, so the set of characters is limited. Still, the styleguide instructs to also use Ĺ and Ń in order to improve the aforementioned automatic transliteration. The rationale for not using any symbols besides them is the scarce availability of etymological characters.

Medžuviki employs two different mechanisms to ease the writing of accented or rare characters. The first one is a large set of clickable buttons that insert special characters at the cursor position. The second one is a JavaScript gadget that automatically replaces some character sequences (i.e. й → ј and zx → ž).

Conclusion

Overall, I’m very optimistic. The technical obstacles seem both surmountable and interesting, and the conceptual problems are kind of stuff that we need to solve anyway. Stay tuned for the next part where I’ll show my Interslavic course prototype and explain the nitty-gritty tech details on how it works.

Meanwhile, let me know what you think. How should the input fields be organized? Will I regret using jQuery and Bootstrap.js? Will someone create the content of the course, or is everything doomed to remain an empty tech demo? Is there an interest in such format of Interactive Interslavic Textbook? Why is it forbidden to lie on the grass? Would Zlatko Tišljar approve of Interslavic language?

Thanks for reading and do viděńja!