Expanding and Using pymorphy2: A Practical Guide

(this is a sidequel to Zagreb sequence)

pymorphy2 is a library for Python (GitHub, whitepaper), intended as an utility for analyzing Russian and Ukrainian text (the dictionaries for these languages are available on PyPi). I think that pymorphy2 is a very powerful tool and would be happy to see it expanded to support other Slavic languages; I think it handles rich morphology well.

I was able to generate a set of Interslavic dictionaries compatible with pymorphy2. In this post I’ll tell how exactly I did it and explain some internal details of pymorphy2 implementation (my examples will come from these three languages: Russian, Ukrainian, Interslavic). I hope my wirte-up could help generate some interest towards pymorphy21 and it’s applications.

I will start with a little interactive applet here. Feel free to play with it.

what is morphological analysis?

(you can skip this section if you already know the answer)

pymorphy2 is a morphological analyzer and morphological generator. That is, it can work as morphological tagger, lemmatizer and an inflection engine. Let’s unpack these definitions.

Lemmatization

>>> morph.parse("программах")[0].normal_form

'программа'

Lemmatization is reducing words to their base form. For example, given a verb “programujete”, lemmatizer should return “programovati” (an infinitive form). This process is needed for standardizing vocabulary, allowing for more efficient analysis and understanding.

Lemmatization should be not confused with stemming. The stemmer standardizes words by removing suffixes, while lemmatizer tries to reconstruct the “true” base form (usually, “lemma” is the form in which a word would be entered into a dictionary2). For example, stemmer will give us something like this by chopping the ending:

okna → okn

vidžu → vid

programujete → program

programah → program

Contrast it with the lemmatizer approach:

okna → okno

vidžu → viděti

programujete → programovati

programah → program

In any case, if you want to build a text search function that doesn’t frustrate users, then you’ll almost certainly3 need either lemmatizer or stemmer. Otherwise, an user that wants to find discussions related to programming will be forced to manually enter “program”, “programa”, “programah”, “programuješ”, and other variants into a search box.

Morphological tagging and inflection

>>> morph.parse("був")[0].tag

OpencorporaTag('VERB,impf masc,past')

Morphological tagging is assignment of various linguistic tags to words, such as part-of-speech (noun, verb, preposition, …), number, gender, case, tense and many others. For example, “napisala” should be tagged as verb with properties of past tense, female gender, singular number, perfect aspect.

In practice, Part-of-Speech tags are very helpful when used as a set of additional features in a wide range of tasks (for example, reducing the size of the text by removing everything except nouns is often useful).

The Part-of-Speech tags are the most coarse-grained part of morphological information stored in a word, but much more is available. The specifics depend on particular language and word involved: in a language with rich morphology, each word could be described with large set of morphological tags (like case, tense, person and so on).

Inflection

Inflection engine (or morphological generator) is a process that reflects the tagging. Given a word and a set of morphological tags, we ask engine to construct a new linguistic form with the specified properties.

An example could be filling the details in an e-mail template while making sure that everything is consistent with the reciepient’s gender: “považeny Mark napisal” but “považena Marta napisala”. Programmatically, it’ll look like this:

>>> isv_morph.parse("napisati")[0].inflect({"sing","past","femn"}).word

'napisala'

>>> isv_morph.parse("považeny")[0].inflect({"sing","femn"}).word

'považena'

How it works

All of these tasks are vital for many Natural Language Processing applications (arguably, it’s even something beyond that. As described by Ray Kurzweil, human technology is created by building tools that help us to build better tools; I believe that, in this sense, a humble lemmatizer is the foundational cornerstone of the entire NLP field).

pymorphy2 does pretty good job with each of them. The library uses pre-gathered dictionaries stored in a particular format; the dictionaries contain each valid form of each vocabulary word. Given a word, pymorphy2 performs a dictionary look-up and retrieves the corresponding information if found.

Being a glorified lookup dictionary may sound like a weakness, but in reality this is a large advantage. Back in 2007, Pavel Šmerk argued for the approach of generating each word form in advance, compiling them into a static dictionary and then using only them for all above-mentioned tasks. This separation of the “analysis” process and the description of data allows for a greater flexibility and transparency; for example, the analyzer and the tools managing the generation of lexemes could be written in different programming languages. Also, the optimized static dictionary gives us higher processing speed and lower size of data.

The underlying data format of pymorphy2 (DAWG) is very similar to the DAFSA format proposed by Pavel (indeed, both Pavel’s majka4 and pymorphy2 are based on the same PhD dissertation by Daciuk).

Storage format

The source data for static dictionaries consists of all word forms, grouped by their lemmas, along with their complete morphological tags (presented in OpenCorpora XML format). For instance, let’s consider the word forms for a lemma like “putnik” (traveler). For brevity, I drop the morphological tags (namely: NOUN, masc, anim) that are the same among all word forms.

| form | tags | form | tags |

|---|---|---|---|

| putnik | sing, nomn | putniki | plur, nomn |

| putnika | sing, accs | putnikov | plur, accs |

| putnika | sing, gent | putnikov | plur, gent |

| putniku | sing, loct | putnikah | plur, loct |

| putniku | sing, datv | putnikam | plur, datv |

| putnikom | sing, ablt | putnikami | plur, ablt |

| putniče | sing, voct | putniki | plur, voct |

We can build the necessary static dictionaries, using just data like this, no additional information about language is required. pymorphy2 can perform this process automatically.

The first stage involves replacing each morphological tag with its numerical ID. This numerical representation makes the subsequent stages of compression more efficient.

The second stage focuses on identifying and extracting stems from the word forms. The stem is defined as the longest common substring shared by all forms of a given lemma. For example, in the lemma “putnik”, the common substring “putni” serves as the stem (note that it differs from “putnik” because of consonant change in the vocative case).

Once the tags and stems are processed, we obtain a set of all possible suffices together with the corresponding morphological tags (so, from our putnik example we can gather 14 strings like k:sing, nomn, ku:sing, loct, če:sing, voct, etc. These strings can also describe other words like umnik and cinik). A Deterministic Acyclic Finite State Automaton (DAFSA) that attempts to describe this set is built and then minimized. The minimal DAFSA not only reduces redundancy but also helps infer paradigms.

A paradigm in pymorphy2 is an inflection pattern for a word. It consists of a set of prefix, stem, and suffix triples, one for each word form in a given set (lexeme). Each word form i can be represented as prefix_i + stem + suffix_i (where the stem is constant across all word forms). If we are given only a word form (as a string), paradigmId and formId, then unknown stem could be inferred.

The end result is saved in several binary files:

paradigms.array: This file stores the paradigm information as arrays of numerical IDs representing prefixes, suffixes, and tags.words.dawg: This file provides a fast lookup mechanism, mapping each word form to a combination ofparadigmIdandformId.prediction-suffixes.dawg: This file keeps track of popularity of each paradigm, grouped by suffices of particular length. This information is used for predicting Out-of-Vocabulary words.

For unknown words, a provisional analysis is suggested (mainly based on the ending’s similarity to other vocabulary words; this heuristic is particularly well-suited for Slavic languages that have almost unlimited capability to stack verb prefixes, for example look at “недоперепил”, “понавыдумывать”, “предрасположенный”, “понаперезаписывал”).

Generating dictionaries

There are some additional steps required to obtain the necessary source files. The first phase involves exporting all necessary data from the Interslavic Dictionary at interslavic-dictionary.com. Currently, the dictionary’s code includes a process for creating a complete “snapshot” of all word forms, used for regression testing. Thus, we needed to implement a new export process (in JavaScript) analogous to this procedure. The result is a text file where each line includes a word (in its initial form), part-of-speech information, and a JSON text with every form of that word along with the required morphological tags.

The second phase is converting the exported text file into the OpenCorpora XML format. This mainly involves adding the correct tags (grammemes) to each form and splitting a single dictionary entry into multiple forms (e.g., dictionary understands (n)jemu (mu) as one entry, but in reality this is a description for three different forms: njemu, jemu, mu). This is a complicated process with specific logic for each part of speech.

Ambiguity

>>> [(p.normal_form, p.tag) for p in isv_morph.parse("metal")]

[

('metati', OpencorporaTag('VERB,impf masc,sing,past,tran')),

('metal', OpencorporaTag('NOUN nomn,masc,sing')),

('metal', OpencorporaTag('NOUN accs,masc,sing')),

('metati', OpencorporaTag('VERB,impf masc,sing,past')),

('mětati', OpencorporaTag('VERB,impf masc,sing,past,tran'))

]

In cases of ambiguity, more than one morphological analysis could be returned (for instance, “dobro” could be a noun, adjective, or adverb); that’s why I write [0] in each code snippet.

pymorphy2 does not attempt to disambiguate possible parses. As a crutch, it keeps frequencies of various word forms and which “correct” parses they correspond to; it orders the possible parses according to their inferred probabilities. This is useful for quick prototyping, but if one needs to improve the accuracy of morphological disambiguation, then these estimates might as well not exist, since taking context into account might change these probabilities quite drastically. Also, these probabilities are gathered using a large manually annotated text corpus, so they are not available for lesser-resourced languages.

Implementing context-aware morphological disambiguation is not particularly challenging task. With a sufficiently large corpus, one can, for example, train a simple SVM model on a corpus of 1 million Russian sentences to achieve over 90% accuracy (a similar approach was employed earlier for Czech). Modern large language models, especially multilingual ones, also perform a reasonably good job of zero-shot disambiguation.

(for example, see this screenshot of my chatGPT conversation. Note the confusion between “stone” and “stones”. Yet it worked out in the end!).

Neural lemmatizers

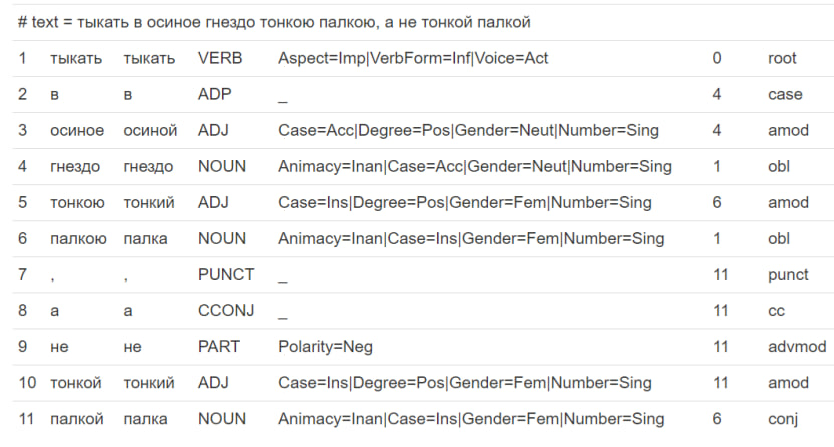

If more advanced language models can handle morphological ambiguity, then why not just use them in the first place, in an end-to-end fashion? The optimal approach is hybrid: combining the strengths of neural-based models with the robustness of static-dictionary-based analyzers. I’ll illustrate it with an example, where the UDPipe models attempts to parse “тыкать в осиное гнездо тонкою палкою, а не тонкой палкой” Russian sentence:

You can reproduce it yourself by visiting https://lindat.mff.cuni.cz/services/udpipe/run.php

You can reproduce it yourself by visiting https://lindat.mff.cuni.cz/services/udpipe/run.php

The first thing to note is the incorrect lemma for “осиное”, which is identified as “осинОЙ” instead of the correct “осинЫЙ”. If the word had a different stress pattern, the ending “-ой” could be correct (compare this to the difference between “запасный” and “запасной”, where two endings coexist). The Russian stress is notably unpredictable, so it’s not surprising that UDPipe missed this nuance.

The second thing is the lack of difference between phrases “тонкой палкой” and “тонкою палкою”: they are indistinguishable in terms of grammatical features. This means the word form is not fully specified, akin to the “they are the same picture” meme. The static dictionaries could contain more precise morphological knowledge, including things like variant forms of Instrumental case endings.

The similar situation exists in other languages. For example, Ukrainian sometimes allows for two dative case forms: “дати книгу Петру” and “дати книгу Петрові”.

As you can see from this example, it makes sense to leverage both approaches; for example, to verify the suggestions of neural-based models against possible parses provided by a static-dictionary based analyzer.

Restoring diacritics

>>> ru_morph.parse("слезы")[0].word

'слёзы'

>>> uk_morph.parse("гвалт")[0].word

'ґвалт'

>>> isv_morph.parse("begajuči")[0].word

'běgajųći'

An additional feature of pymorphy2 is the capacity to be applied as a limited spellchecker, mainly used for restoring missing diacritic marks in the contexts where they are optional. Let’s take an English word “resumé” as an example: the “proper” way to spell this word requires using “é”, but writing “resume” isn’t considered a mistake. Here we have a e≈é pair with a notable property of asymmetry: a word being spelled using “e” leaves some ambiguity about whether the “proper” spelling uses “e” or “é”, while the opposite guarantees that the writer really meant “é” to be used. Such cases are rare in English, but is much more common in other languages (e.g. German ss≈ß) and/or other time periods (e.g. German u≈ue/uͤ/ü).

Borrowing the terminology from Zaliznyak5, I’ll call letters like “é” marked and their counterparts unmarked; likewise, the words could be written using either simplified or complete orthography. The pymorphy2 dictionaries use complete orthography, but the user inputted text could be written in both simplified and complete variants: if a match can be obtained by marking some letters, then it’ll be returned (perhaps, together with the original spelling, if it is also found in the dictionary); but a match obtained by “downgrading” letters to their unmarked counterparts will never be considered. The technical implementation in pymorphy2 was mainly motivated by the Russian (е≈ё) and Ukrainian/Belorussian/Rusyn (г≈ґ) orthographies and allows to handle such cases automatically with negligible overhead.

The case of a single “marked” variation of an “unmarked” letter is quite common (for example, both Bulgarian and Macedonian have и≈ѝ and е≈ѐ pairs), but many orthographies require more sophisticated logic for diacritic restoration. Speaking of other Slavic languages: Czech has u/ú/ů and e/é/ě; Slovak has o/ó/ô, a/á/ä, and l/ĺ/ľ; Polish has z/ź/ż. The Interslavic language even has three “marked” variations of a single letter: e/ę/ě/ė. Not to mention the several horrifying tonal transcription systems used for Southern Slavic languages. Sadly, pymorphy2 was not able to handle these cases “out of the box”.

Luckily, the problem turned out to be amenable to a relatively straightforward fix6 which I implemented in a fork, so make sure to update your dependencies (both pure-Python and C++ versions are available). Porting this to JS is on my ToDo list.

Another technical limitation still remains: you can only map single letters into single letters. That is, no dž -> đ, no я -> ја and definetely no ње -> ньје. Note that this limitation includes cases like “base character + Unicode combining diacritics”, which pretty much forces us to use ľ ť ď Interslavic orthography instead of ĺ t́ d́ orthography (and I use dʒ instead of đ in order to allow for the equivalent of dž -> đ substitution).

ports to other languages

I previously mentioned an advantage of separating the analyzer from the word form generation tools: they can be written in different programming languages. The dictionary files used by pymorphy2 are in a specific format that is not inherently tied to pymorphy2 or Python. This consideration is not purely theoretical, as there are Java (jmorphy), JavaScript (Az.js), and Rust (rsmorphy) implementations of pymorphy2 that work with the same .dawg format.

The JavaScript port is particularly important for Interslavic, as applications written in JavaScript are an important part of Interslavic software ecosystem. Namely, various inflection scripts written by Jan van Steenbergen and their modifications from the Interslavic Dictionary team de-facto serve as the reference implementation of morphology. As noted above, replicating this work is not reasonable; it is better to export the words and their forms, allowing us to integrate any future changes to the vocabulary or rules.

Still, the ability to use .dawg files in Javascript (or, even better, in TypeScript) will be very beneficial. For example, it can potentially enhance search functionality in the Interslavic Dictionary (allowing user to input an inflected word and get a translated word in a corresponding form in search results) and allow a fully client-side spellchecker.

Unfortunately, Az.js library turned out to be not completely compatible, as it uses different compression format for DAFSA. According to the author, this format allows binaries to be 25% more compact. However, the scripts for building these dictionaries and the tool for this compression are not yet open source (and unlikely to ever be released), and no complete specification of the new format is available.

Together with castaval and sonic16x, we extensively rewrote Az.js to make it more compliant with pymorphy2, also porting it to TypeScript. That’s exactly the thing that the interactive gadget above demonstrates.

As an aside, if I were to generate a set of dictionary files for another Slavic language, I would start by gathering Wiktionary inflection table data. Wiktionary uses Lua to generate such tables from an ultra-short description. For example, the string {{bg-conj|мо́га<irreg.impf.intr>}} (for Bulgarian verb мога “to be able”) expands to a conjugation table containing over 56 entries. Therefore, unless someone wants to port code from Lua to Python or JS and regularly incorporate upstream changes, the approach of separating static dictionaries from generation code seems to be the only viable option.

-

Or at least towards other similar approaches like

majka/morphodita. ↩ -

The lemmatization of verbs usually involves transforming various conjugations into their infinitive form. However, Bulgarian/Macedonian is an interesting case: these languages do not have an infinitive form of verbs anymore. In them, the dictionary form is first person singular. For example, lemma for “програмираш” would be “програмирам” instead of a non-existing “програмирати”. ↩

-

Why “almost”? Because, theoretically, you can survive without them if you use something like embeddings or LLMs. That is, if you can tolerate a 25-fold increase in disk space and 200-fold increase in query latency. ↩

-

why do I use

pymorphy2instead ofmajka? I have no good answer to this. I just happened to be more familiar withpymorphy2, since it works natively with Russian whilemajkais intended to support Czech. A more detailed comparision of their capabilities could be an interesting topic. ↩ -

originaly used in his analysis of Old Church Slavonic manuscript named «Merilo Pravednoye». The book distinguished between two /o/-adjacent sounds: /ô/ (written with either Omega or “plain” O: “закѡн” and “закон”) and /ɔ/ (written with “plain” O). ↩

-

A more detailed explanation requires the knowledge of

pymorphy2’s internals (if you are curious: see the section titled «Working with “ё” and “ґ” Characters Efficiently» and note that there’s no real reason why we cannot extend traversal rules by adding a set of optional transitions instead of a single optional transition). ↩